A Man's Hands

In Four Parts

A Man’s Hands

One

Evenings for our little family find us on the bed with the two dogs, who comprise the portion of our family still at home—and while we watch whatever movie we’ve selected for the night, we invariably hold hands. In fact, the hand-holding is not in the least secondary to the movie-watching. For my wife and I, finding something to watch night after night is a never-ending challenge, so the bar we set is low. Our official object is to find something “watchable” (the golden mean between her taste and mine) and, as often as not, amounts to no more than a disaster flick with lots of buildings demolished by earthquakes or by tidal waves—in truth, one of our favorites. When Tolstoy wrote “All happy families are the same” he was proposing a moral dimension to happiness that some, no doubt, will find irritating because it contradicts everything they were persuaded to think about happiness. But at my age, there’s nothing for which I’m so grateful as my beautiful wife, who loves me for indecipherable reasons, and for whom it has become my everyday pleasure to serve in whatever way I can to make her happy—merely because her happiness is my happiness. This simple wisdom came to me on wings, but so late in life, I’m lucky to have received it at all.

I wish when I was young I’d kept a list of all the “watchable” movies I had seen, but, when I was young, I was too much of a snob to see the usefulness in “watchable.” The movies we have seen and forgotten is now a vast library, and we’re never more delighted than when our memories are completely blank about some promising title. Every six months or so, while we’re watching a movie, my wife will suddenly let go of my hand and place her hand beside mine as if to compare them, and she will say (with an imperative in her voice): “Look at how much larger your hand is than mine! Look at your thumb and my thumb!” This statement is always made with a kind of irrepressible female delight that requires some kind of acknowledgement from me along the lines of: “Yes, indeed, my hand is quite a bit bigger than your hand!” And though my hand is certainly not twice as big as hers, it is at least a third again larger. And for a moment we both look at our hands together, fully conscious of the fact that it is entirely consistent in the nature of men and women that a man’s hand is the much larger of the two. Just as it is in the nature of men and women that she should delight in that fact. And he (if he were honest with himself) would also admit to a kind of joy in the more diminutive essence of femininity, somehow intensified by its compactness.

Two

I can’t look at my hands without seeing dad’s hands, big and bony with heavy knuckles and the fragile white skin of old age. Although he’d worked his way as a laborer through college, for the remainder of his life, his hands did little more than scribble notes for sermons on yellow legal pads in his illegible cursive. Not to say he wasn’t a hard worker. He racked up 60 hour work weeks on a regular basis and I can’t remember him ever loafing around the house. That was a fact of life for us kids and we had family jokes about it. Dad was six foot one, an inch taller than me, and his hands were an inch longer as well. A tall, broad-shouldered man, he would have made a crackerjack carpenter, and maybe there was a remote corner in his heart that could have been happy as a working man. His dad had been a roughneck in the California central valley, and endured all the hazards of working an oil rig in the thirties. But dad as a boy had seen his own dad break his back in a freak accident, and maybe that calamity was enough to push him in another direction. Like me, I don’t think dad ever broke a bone himself, not even in those last years and the many falls he took at ninety, keeling over like a felled tree, sailing backwards down stairways, tilting sideways off porches, bearing all those huge and terrible multi-colored bruises, but all his bones intact.

Although we were middle-class and Dad was hardly folksy, he did possess a habit of directness that was decidedly not managerial. A strain of a working-class ethos ran through my childhood, so that when I later entered the world of construction, I felt strangely at home. Every Sunday morning mom would fry a steak for Dad as he pulled together the notes he had been pondering all week, an hour before he climbed into the pulpit. And though he was in many ways what some people call “a public man” I still have two memories of being carried by my father when I was very young. Once when I had fallen asleep in the back of the car as we drove home after a long evening of visiting friends. All I remember is the sensation of being carried across the dark suburban lawn, the radiance of the porch light at the front door, and the softness of my own bed. Another was of him anxiously rushing me in his arms out of a rented cabin into the snow to rouse me after he suspected the heater in my bedroom had begun to produce carbon monoxide. Wet snow on my face is the only detail I can produce. Both memories are so brief and precious for their rarity, of being in Dad’s hands.

Three

It was a kind of lunch hour contest with the crew gathered around a chunk of beam to see who could drive a three and a half inch nail with a single hammer blow. Back then, my boss liked to use “box nails” because their slenderer shank was less likely to split the framing lumber than the thicker “common” nails. But the plumbers and electricians, who had to occasionally borrow a handful, absolutely hated them because of the box nail’s propensity to bend. And it was common to hear the plumber cursing the nails out loud—my boss got a sadistic kick out of it. In fact, that tendency to bend was so pronounced that to drive a three and a half inch 16d box nail, it was almost mandatory that each blow of the hammer had to vary minutely in mid-air to compensate for the slight but inevitable bending of the nail as it sank. This process was known among carpenters as “talking” a nail in, and those infinitesimal variations in a hammer swing could not be planned, or thought about—it was just something that you learned to do after driving (and bending) some thousands of nails. This reality adds some context to the pedestrian use of the word “hammer” as a metaphor for an indiscriminate use of force. On the contrary, the hammer swing of a real journeyman was a thing of beauty, flashing and alive—as the hand in mid-swing made tiny adjustments to follow the changing bend of the nail. By contrast, the hammer-stroke of a homeowner or a movie actor is always an embarrassment of rigid control, usually choking up on the handle to further constipate the flowing motion of the arm. Hammers back then had about three manufacturers so I never used anything heavier than a standard twenty-ounce Vaughn with a hickory handle. To sink a 16d brite box nail with a single blow, you were required to focus not just on the nail, but on the slight swirl in the center of the head, and the hammer-stroke would begin at your ear, and rallied all the muscles of your arm and shoulder in a whipping motion, a three or four foot swing that could make a three and a half inch nail vanish Houdini-like into the wood beam.

Those raw first months on the jobsite, everything that I attempted to do was cloaked in darkness, and I could not shake the feeling that my incapacity was especially flagrant for some mysterious and tormenting reason. I don’t know how many times I’ve heard a man explain to me with false humility: “Well, I’m just not handy,” as if his lack of handiness was in some inverse relation to his IQ. My only choice was to smile sympathetically because I knew nothing was going to change his mind. As for me, I had put myself into a situation—a job—in which I could either quit or persevere till someone fired me, and believe me, I came close to quitting. It was like trying to speak in a foreign language, mouthing words that would not come. I was in my late twenties and had little experience of the kind of transformation that comes of repeated effort and repeated failure. But over time, as my body became stronger and tougher, my hands began to follow the pathways that always accompany one’s certainty of purpose, and the change that I had not expected finally arrived: finger by finger, lamp after lamp popped on in my head, like the streetlights along a residential block after dusk. If a man seeks to understand an object in the material world, he puts his hands upon it. A man’s hands are the expression of his venturesomeness—are his agents of inquiry. The prominence of a man’s chest may proceed him into the unknown, but it is his fingers that lead him through the dark. On the construction site, a man’s hands were always front and center, where a moment of misdirected vigilance could result in crushed fingers, cuts, abrasions, bruises, and splinters never-ending, one barely healed before another would take its place. I got so tired of removing splinters, I finally just let them fester because I knew eventually they would emerge in their own time. An injury to a man’s hands had to be constantly accounted for, and worked around, an impediment to the swell of his mind on the work at hand, and like an injury to consciousness itself. On the subject of the Pequod’s carpenter in Moby Dick, Melville writes: “…he did not seem to work by reason or by instinct, or simply because he had been tutored to it, or by any intermixture of all these, even or uneven; but merely by a kind of deaf and dumb, spontaneous literal process. He was a pure manipulator; his brain, if he had ever had one, must have early oozed along into the muscles of his fingers.”

Four

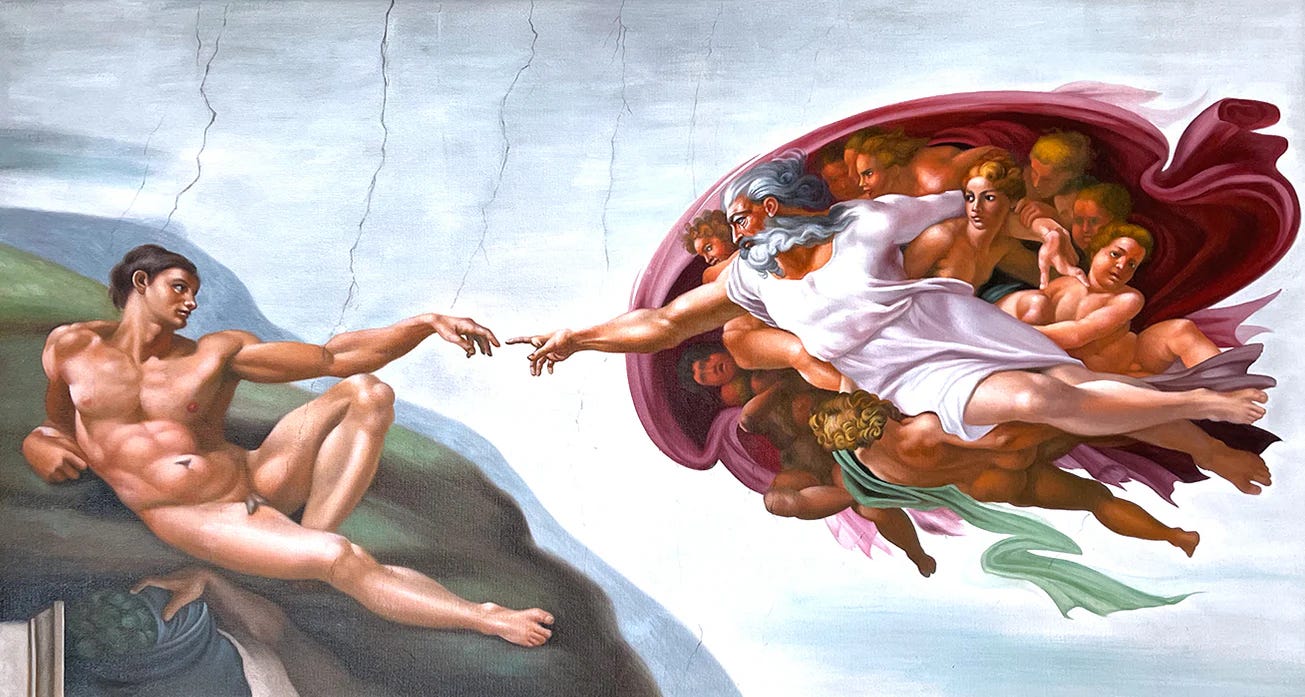

Who hasn’t seen The Creation of Adam, the fresco by Michelangelo on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel? It is now more of an internet icon than a painting in the real world. A few clicks on my keyboard and a thousand reproductions materialize, and not the least are the close-ups of the hand and fingers of God reaching for the hand and fingers of Adam. One superior quality of visual art is that anyone with eyes can participate in its explication. This would be true for Michelangelo’s Adam, except for the fact that the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is nearly seventy feet above the floor, and even had you traveled all the way to Italy, you could not see its detail without the aid of binoculars. Nevertheless I find it somehow heartening that Michelangelo didn’t paint his fresco to be seen at a distance, but painted it how he saw it, from where he lay on his back on the wooden scaffolding pushed up against the ceiling. As Adam reclines away from God, his arm is stretched toward his maker, but not urgently, the fingers are still slightly curled and passive with indifference or ignorance, as if he was not completely aware of the meaning of the moment. His muscles, however, are enlarged, even swollen with inert potential—and his eyes, directed toward his creator, are ambivalent and feminine. In contrast, God is action incarnate, his whole body is reaching out for Adam, his arm extended, his forefinger straight, his eyes directed toward the achievement of contact between their fingers, which, in the fresco, are yet a few centimeters apart. The moment Michelangelo has chosen to depict, which is the transubstantiating equivalent of the breath of life between the first man and his God, is revealing because it’s evident that, while Adam’s fleshly manifestation is entirely complete—is, in fact, robust—the creation is not yet fully accomplished.

My daughter and I share a birth month—in fact, her birthday is the day before mine. She was our first child, my wife’s labor took days, and we ended up in the ICU, where true to type, I paced the halls of the hospital. My wife and I had been six years married when I realized I could no longer withstand her forays against my resistance to having children, which was never a general resistance, but simply a kind of stalling for time. Now, I’m not so sure what I expected to happen over that time. As I paced the hospital halls, the future in front of me was charged with excitement and fear, even if my ambivalence was still ascendant—an ambivalence that would be overthrown quite easily in a matter of hours. After two long days at the hospital, her labor intensified, and as we approached the midnight hour, my wife became determined that the new baby and I should have separate birthdays, and as a result of this determination, my daughter was born shortly before midnight. My exhausted wife fell asleep immediately. They wrapped the baby up, and to my amazement, put her in my arms. Nothing could have been more shocking than how small and vulnerable she was, only a tiny bit bigger than my hands. I felt entrusted with a high responsibility, of which I was barely deserving, especially given my earlier ambivalence, now revealed in all its absurdity. What could be more quotidian than babies distributed like candy into the world? And yet she was so very beautiful, and so perfect—and for the next few hours, which was my birthday, I wandered the halls of the hospital and shared my new daughter with anyone with the remotest interest in a newborn baby, which was almost everyone. I was in a swoon, and fell in love so entirely, and so without qualification, that I was overwhelmed by a dream of joy, and a determined resolve, that I had never in my young life experienced before.

(Dear Faithful Reader: Working Man is 100% AI-free and free to all subscribers. If you liked this post, please let me know, and also check out some of my recommended older posts: Men’s Bodies, Immortal, Working for a Living, Fathers and Sons.)

This is what Substack was designed for. This essay is its own ceiling fresco masterpiece.

Marvelous. Just marvelous. And heartwarming.