Heavy Equipment: The Driller

You could hear it from a mile away: the slap of an enormous pile of lumber hitting the street, its steel bands popping, and a few 2x4’s tumbling to either side of the load. For me it was the sound of getting back to work. The driver would crank the rear end of the load off the big steel rollers on the flatbed of the lumber truck—then he’d fire up the truck and drive out from under the load. Boom! Unless the pavement was sloping or wet, the huge stack stayed where it fell, but more than once, I saw a whole pile in slow motion slide another thirty feet before it actually stopped. And more than once someone was tasked with rebuilding a neighbor’s mailbox. A lumber drop was a driver’s art, one that we valued, so we knew all the drivers by name. On one occasion, a driver forgot to set a parking brake, and as he stepped down from the cab door, both the truck and load took off, rolling backwards a hundred feet down the hill and through the entry of a house—a house we had built a year earlier. The owners were at work, so I wasn’t around when they got home to see the fully loaded lumber truck lodged where their front door had been. The unexpected repair job took us from our own project for a couple of months.

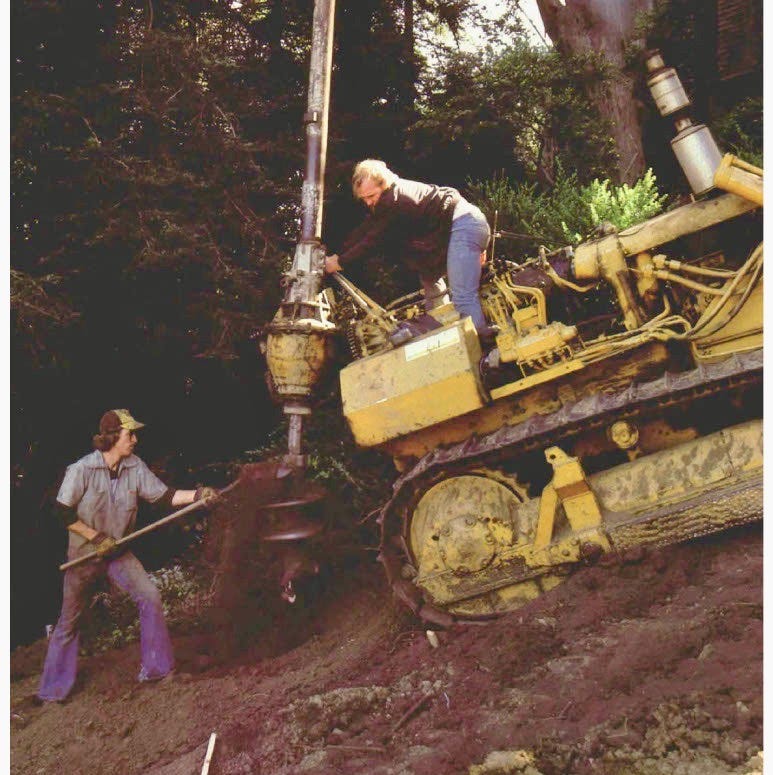

The presence of heavy equipment was uncommon enough to always be mildly exciting—the scale, the noise, the power—but by the time the equipment had done its work and was gone, we welcomed the quiet, too. Concrete trucks, concrete pumpers, backhoes, and excavators. Sometimes we needed a crane. Forklifts were useless on our lots. But we always needed a driller in the construction of the foundation. High up on the ridgeline of the hills was a thousand feet above the flatlands of the east bay, and ten degrees cooler. One cold November morning, when the driller showed up, he informed me that he was making two hundred dollars an hour “danger pay” because the lot was so steep. I was making a tenth of that, but I didn’t have to sit on the bulldozer. Jeff and I had laid out the property lines, built the batter boards, pulled up all the strings, and spotted the location of each pier hole with a wooden stake. Something like fifty holes, twenty feet deep, sixteen inches in diameter. When filled with concrete and steel, they would become the support for the concrete grade beams on which the weight of the house sat. And it was true: that particular lot felt steeper than anything I had ever done. Small sections felt almost vertical, although probably the average grade was about forty-five degrees, which doesn’t sound so bad till you’re standing on it. Drilling days always alternated between boredom and high anxiety. Anxiety when the dozer, struggling on the hillside, would take out a row of stakes that I had to replace while he waited at two hundred dollars an hour. It always meant moving him out of the way (knocking out more stakes in the process) so I could pull the strings, drop the plumb bob, and set the stakes. Other than that, I just stood around, watching the driller drill, and feeling the edge of the wind. The dozer gave off a heat that warmed the air three feet around itself, and if I was lucky I could stand there in that zone, but otherwise I just froze. I don’t think Jeff had any idea of what kind of chaos the bulldozer would bring to our neat little rows of stakes.

The bulldozer was a D-9 CAT specially modified for drilling. On one end, the drilling unit was attached directly to the bulldozer’s body. On the other end of the dozer, on its wide bucket, a winch was welded that enabled the bulldozer to move up and down the slope on a one-inch steel cable that kept the bulldozer from pitchpoling down the hillside. Without the winch, the bulldozer was helpless. The cable went from the bulldozer’s blade up the hillside and was looped around a big piece of telephone pole (a “deadman”) that stood in an eight-foot-deep hole drilled on the far side of the road, up against a sandstone cliff. When cars passed, they simply bumped over the one-inch cable. Before we were finished, the operator had to sink four holes to enable the bulldozer to move laterally across the slope. An excavator, by comparison, was much faster setting up on a hole than a bulldozer, but I never saw an excavator with a winch. So the whole process was harder, slower, and messier because the bulldozer took time to set up perfectly over each hole—slipping, sliding, and grinding on the hillside, one hole at a time, and relentlessly tracking up and down the forty-five degree incline. With twenty foot deep holes yawning everywhere, just walking over the treacherous, loose, new landscape required extra care. No one ever fell down a hole, but it seemed possible.

The auger of a drilling rig was mounted at the bottom of a tall, upright, square shaft known as the Kelly Bar, thicker than your arm, that spun the auger, and plunged it deeper into the hole. Ideally, the auger went straight down, turned until its spirals were laden with dirt, then returned to the surface, and spun again in high gear so the dirt was flung outside the opening of the hole. Then a helper “cleared” the hole with a shovel, so as little dirt as possible fell back in. He knocked off whatever mud had clung to the auger, then it descended into the hole again. Sometimes, water from a hose was used to get drier dirt to congeal onto the auger. Occasionally, we’d run into hard rock, and the bulldozer would “stand” on the augur for a while as it carved. If that went on for a half hour or more without significant progress, the hole was marked “refused” on the plans, and it was a problem for the engineer. The ideal hole, cut through softish sandstone, went very quickly, a half hour a hole, but ideal was rare, and every hole had its own problem. If the soil was too soft, the augur might cut wide, making it hard to clear the loose dirt. Sometimes you’d hit something hard right off which would divert the auger from its location. The load-bearing capacity of a pier hole was calculated based on the friction of the concrete on the sides of the hole, not on its bearing on the bottom. However, sometimes we managed to convince the engineer to change a hole from a “friction pier” to an “in-bearing pier”which saved some time “standing” on a single hole for hours, which occasionally happened, if an engineer was insistent.

The biggest problem was simply getting the cumbersome bulldozer on the slippery slope set up with precision and stability over a stake. Very quickly, the contents of the drilled holes—the yards and yards of dirt—became the unstable surface of the hillside which the bulldozer had to negotiate using the winch and its tracks in tandem. A “yard” of anything—of dirt or concrete or gravel—is equal to 27 cubic feet of material. Oftentimes the tracks would spin wildly in its effort to get from one place to another. Of course, a bulldozer cannot move perpendicularly to the slope without rolling over, so, in order to move sideways it had to winch up and down the slope several times with his tracks at a bit of an angle to the fall line, creeping sideways. This reality was not kind to the fragile rows of stakes Jeff and I had so painstakingly positioned. The slightest re-adjustment of the dozer over a hole spun up huge mounds of dirt. Occasionally the enormous metal monster might manage to straddle a row of stakes but more often it did not. The only solution I could come up with was to drive the stakes all the way flush with the ground, and dig out a four-foot diameter area so we could recess a section of plywood, “a hole cover,” over the stake. That seemed to help, though sometimes we’d have to remove wheelbarrows of dirt off the plywood cover to find the stake beneath. Eventually, those same hole covers were used to protect a completed hole from filling with dirt (and to prevent curious neighbors from falling into the holes.)

All I was doing was “supervising” but it was exhausting just standing in the roar of the dozer and watching the Kelly bar spin in and out of the hole, dripping with grease—the sexual metaphor of it so blatant it practically shouted. In the beginning I was careful not to stand directly beneath the dozer, in case the winch cable snapped, but the tireder I got, the less I cared. Sometimes we’d hit hard rock and the hole would veer off of center. Sometimes there were short sections of actual cliff for the dozer to negotiate. Sometimes a dozer track spun and ripped into the ground, so that all my careful protection of stakes was in vain—and the dozer would have to pull all the way up the hill and out of the way again. In the middle of the third day, the auger of the dozer struck something hard down in the hole. This was something different, though, and the blades of the spirals on the augur seemed to hook onto something big that began to revolve around the Kelly Bar. The operator fiddled with the controls, and the next second, the augur unearthed a huge round waist-high boulder, that he attempted to manipulate with wildly flipping controls onto a tiny flat spot next to the hole, as the helper tore at the ground with his shovel to widen the flat section. When the operator got the boulder poised, instead of leaving well enough alone, he dropped down, and tried to wedge it more securely with the blade. At this, the boulder rebelled, rolling in slow motion around the corner of the blade, and down the hill, picking up speed, as the helper desperately tried to stop it. I just watched. It was a two-ton boulder—he wasn’t going to stop it. The boulder just shrugged him out of the way and I looked down the hill at the path it would take. For a hundred yards, it was a straight shot from where we stood to the house on the street below. There was some white Pampas brush in the way and then the back yard fence of the house, which I gave zero chance of stopping it. We waited for the worst to happen, but then the boulder disappeared into the Pampas brush, and never emerged. The fence was untouched. We couldn’t believe it—somehow the Pampas brush had stopped it? That was all I could think of, which didn’t seem possible. It occurred to me in that moment that it was my responsibility to go down the hill and check things out, but it was almost the end of the day, and for the operator, the end of the job.

He drilled the last two holes and I helped him pack up and leave. We removed the telephone pole, filled the deadman holes, and I busied myself covering all the drilled holes with plywood, staking the covers as well as I could. I knew I couldn’t leave until I found out what had happened to the boulder, so I climbed down to the bottom of the lot into the Pampas weeds, which were, as I had guessed, more frail than stalks of corn. But there in the middle of the pampas thicket, I found the boulder. It had landed into a very small four-foot square pit not much bigger than the boulder and about as deep. It looked man-dug, but whoever had dug it had done it a long time ago—it was full of weeds with the boulder sunk into its middle, hairy with roots and loose dirt. There was no other pit like it in the area. The giant boulder had emerged from the ground, and rolled down the hill to find its final resting place in the one hole on the hillside big enough to hold it. I looked down at the undamaged fence and the back of the house it would have taken out—it looked like a dining room. I climbed all the way back up to my truck and drove home. And for the rest of that project, I never again went to look at the boulder in its tiny pit. But I have no doubt, it’s still there to this day.

(Working Man is 100% AI-free and free to all subscribers. Posts every other Tuesday— as well as I can manage. Memoir chapters alternate with other topics. Thanks for reading!)

Is that picture of the actual dozer/auger rig that you worked with? That's a very old D9 - Cat went to elevated sprockets in 1977, and that also looks like cable controls. I cut my teeth on D10's and D11's in the late 80's, and our pit development work sounds very similar to what you describe here - we had to do some track repairs on D11's stuck and half buried on unstable 45 degree slopes!

I once had an operator tell me that you couldn't roll a dozer...but I've seen multiple dozers on their sides, and belly up, so I'm not sure what gave him that idea.

We used more rockbreaker attachments than augers, often (as you describe) on excavators. But we also stuck a rockbreaker on the front of an old 992 wheel-loader, with a modified boom - that caused some significant heartache, getting it to work reliably - but it was a good stable platform.

Great piece, again - I could smell the diesel and hydraulic oil...

retired now, living in Montclair so love the stories. in and out of construction work in one way or another my whole life. keep the stories coming!